2nd & 3rd Revised Editions copyright © 1977, 2016 by Theosophical University Press. All rights reserved. This edition may be downloaded for off-line viewing without charge. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission of Theosophical University Press.

Foreword to the 2nd Edition

Chapter 1. Cycles of Manifestation

Chapter 2. Evolution and Transformism

Chapter 3. The Evolutionary Stairway of Life

Chapter 4. Man the Repertory of All Types

Chapter 5. Proof of Man's Primitive Origin

Chapter 6. Man and Anthropoid — 1

Chapter 7. Man and Anthropoid — 2

Chapter 8. Specialization, Variation, and Speciation

Chapter 9. The Moral Issues Involved

Chapter 10. Reincarnation and Evolution

Chapter 11. Karma and Heredity

Chapter 12. Man's Body in Evolution

Chapter 13. Man's Inner Centers

Chapter 14. Lost Pages of Evolutionary History

Appendix 1. "The Antiquity of Man and the Geological Ages" by Charles J. Ryan

Table of Geological Eras and Periods

Appendix 2. "Theosophy and the New Science" by Blair A. Moffett

This 3rd Revised Edition is to some extent an abridgment, retaining chapters focused on human evolution while omitting material that is dated, repetitive, or treated in the author's other writings. Here he develops the themes of nature's cyclic evolutionary pattern, of the inner cosmic origin of all her kingdoms, and of "Man" as having always existed — that humanities from past universes have left their impress on the mind-fabric of nature, providing the architectural forces shaping not only modern man, but all developing life.

It is perhaps noteworthy that Man in Evolution originated as radio lectures just two years after the 1925 Scopes "Monkey Trial" in Dayton, Tennessee, which pitted Darwinism against Biblical creationism, excluding more philosophically-reasoned approaches to evolution and spirituality. As mentioned in the 1976 Foreword below, Appendix 2 summarizes more recent work in physics, chemistry, and the life sciences, confirming much that is postulated by the ancient wisdom-tradition. In the several decades since then, research has of course considerably deepened and widened the scope of the great evolution mystery that is Man. For further study, some additional titles are appended to the Bibliography.

November 2016

Since its publication in 1941, Man in Evolution has had a particular appeal for students seeking to relate the theosophic approach to evolution — seen as a cosmic process reflecting itself in the human sphere — to the theories propounded in the main by Charles Darwin and his followers. Today, archaeologists and paleontologists are daring to take a fresh look at fossil findings, so that firmly-established views as to our human origins are undergoing radical change. Those in the vanguard of evolutionary thought do not look upon man as the descendant of monkey and ape but, on the contrary, as their antecedent, if not their half-parent.

This is calling for a major reversal of psychological outlook for many, so conditioned have we been from childhood to think of ourselves as having evolved solely through physical mutations which, by some unexplained random leap of consciousness, metamorphosed us from a witless, arboreal creature into the thinking, artistic and creative entity we know as Man.

Not so for the writer of the present volume. Gottfried de Purucker, author and educator, had since youth been a dedicated student of both modern theosophic thought and the traditional wisdom of ancient peoples concerning the origin and destiny of worlds and of the human species — teachings which confirm man as a divine being of immense antiquity, rather than as a recent emergence from lower stocks.

"Man is his own history," says the author, meaning by this that he carries within him the entirety of an aeons-long past. A cosmic entity, he enters earth as a returning pilgrim in process of becoming, of bringing into actuality that which is potential, hidden within his inmost essence, and which, given time and the appropriate environment, will flower into fullness. For evolution is no chance happening, but an orderly manifestation of the spiritual-intelligent drive inherent in the universe and therefore intrinsic to all life-particles. Not an atom, cell, human being or sun, could exist unless at the core of each were divinity.

With this as background and foreground of his thought, Dr. de Purucker examines critically the dominant evolutionary hypothesis, to see where theory merges into fantasy, where concepts still unproven have hardened into "facts" without adequate basis in nature. Rigorous analysis, cogent argumentation, supported by clear-cut testimony of anatomical structure, bring conviction that the human line is of extremely ancient origin, the most primitive of all the mammalian stocks and hence must have preceded, not followed, the more specialized apes and monkeys.

With knowledge of biological fact, the author regards man's essence primarily as a divine spark seeking imbodiment in ever-fitter instruments through each of nature's kingdoms. The dignity of humanhood is thus enhanced, giving our lives here on earth majesty and purpose.

The material in the present volume originally stems from a series of lectures titled "Theosophy and Modern Science" given by Dr. de Purucker at the Theosophical Society's headquarters at Point Loma, California, from June through December 1927, and broadcast live over San Diego radio station KFSD. In 1929 these lectures were published, without editing, under the above title. The edition soon sold out, and the book remained out of print for several years.

In 1941 the author issued a somewhat condensed version as Man in Evolution, the work of rearrangement having been in large part due to the labors of Helen Savage Todd, whose editorial assistance Dr. de Purucker acknowledged with "grateful and genuine appreciation." For that edition, however, he saw no reason to bring forth "newer and later scientific arguments in favor of the theosophical doctrines," as he regarded those he had drawn upon for his lectures a decade earlier mainly as background for the "theosophical picture" he wanted to portray. To him, the principles upon which theosophy is founded are rooted in the structure of nature herself and therefore are ever-enduring. In an Appendix he did incorporate certain forward-looking statements from noted anthropologists and anatomists of the period (1930-1940), but in view of the greatly extended time span now afforded man by paleoanthropology, reaching back into the millions of years instead of a mere few hundreds of thousands, this material has been replaced in the present volume with two new entries:

Appendix 1: "The Antiquity of Man and the Geological Ages" by Charles J. Ryan, which provides a succinct explanation of the geological ages in relation to the "rounds" or cycles and the various "root-races" traversed by humanity. Also included is H. P. Blavatsky's table of approximate time periods placed alongside the contemporary time scale of eras and epochs as generally agreed upon by geologists.

Appendix 2: "Theosophy and the New Science" by Blair A. Moffett, which assembles current findings in physics and the life sciences, supplying valuable scientific data for comparison with and analysis of Dr. de Purucker's presentation of man's spiritual and racial origins.

Man in Evolution offers a unique approach: it treats of evolution from within and above, rather than from without and below. Instead of relying on missing links among fossil remains, it provides the one valid missing link: that of the spiritual or dynamic factor, the divinely impulsed intelligent entity at work in, through and behind all processes of birth, growth, maturation, decline and death. To the author, man's place in the cosmos is axiomatic, not something in need of proof.

The editor of the present revision of this important volume acknowledges with gratitude the assistance rendered by all who helped in its preparation, with a special word of appreciation due those who undertook the exhaustive research required to check all quotations from original sources.

Grace F. Knoche

November 1976

Pasadena, California

Among the most momentous questions that every thinking person asks are: Where do we come from? Who are we? And where do we go at death? We come here on the stage of life as it is on this planet earth. We make a few gestures and movements, suffer somewhat, rejoice somewhat, are ill or well, and then we pass off that stage, which apparently knows us no longer, nothing but a memory of us remains, and perhaps not even that. Yet in a universe governed by law and order and progress, the sufferings that we have endured, the joys that we have had, the ideals fulfilled and unfulfilled, must have had their origin somewhere.

It is questions like these that occur to the thinking mind when it also reflects upon the nature, origin, and destiny of the worlds which bestrew the spaces of infinitude. Whence came they? What are they? What is their destiny? They are questions which must have answers. The mere fact that these things are, shows that there are answers to be had somewhere.

What is the method by which worlds and we men and other beings evolve? What is the method by which we come from the invisible into the visible, out of the darkness, as it is to us, into the light? The method by which worlds and men and all the rest seek expression is a cyclical method, that is to say, a procedure in and through cyclical progress. The great seers of the human race, who were and are the most fully-evolved men that the globe has yet produced, have put it on record and handed it down to us as the guide of our life — that method works somewhat as follows:

Beginning as an unself-conscious god-spark, each entity, each spirit-soul, each monad — for there is a monad at the heart of every individual entity — seeks self-expression and the building up of appropriate vehicles through progress, until finally such method produces a vehicle which can express, more or less fully, the spiritual energies and forces of the monad within. When this point of progress has been reached, man then from an unself-conscious god-spark has become a self-conscious god, a self-conscious spirit, because he self-consciously manifests the sublime powers and faculties of the monad within, and he likewise lives in appropriate realms of existence where he builds for himself vehicles capable of expressing somewhat of the sublime inner faculties.

So it is with all the hosts of lives, because the entire universe is composite of these hosts, each one of which holds its character and its individuality and its own particular origin, this last in the spiritual world, yet each following its own particular pathway of progress. All come from the central Fire. Yet from the moment of their issuance therefrom, each such spark follows its own especial line. Why? Because it is a treasury of sleeping faculties particular to itself; in short, because it is ensouled by its own characteristic force, its own individuality, its own svabhāva, to use the Sanskrit term. This amounts to saying that each such god-spark follows a path of self-development eventuating in self-directed evolution, when a vehicle capable of expressing self-consciousness has finally been built to enshrine the god-spark working through it.

So again is it with the worlds, the universes. They issue forth into physical manifestation from the bosom of great Mother Nature as "nebulae" composed of most ethereal matter, matter so quasi-spiritual that we cannot see it as it is, either with our physical eyes or indeed with our physical instruments as aid to our vision. There are, at the present time, uncounted hosts of such spiritual universes, not yet visible to us, because our physical organs have not developed the subtlety of vision enabling us to see things so much more subtle and fine and spiritual than the gross physical matter that our eyes may take in and our brain-organ understand.

In time each such world as it passes on its downward and cyclical way into the matter worlds, seeking expression and therefore knowledge on and of these lower planes and in these lower spheres, undergoes concretion or materialization of its substance, partly by the gathering into itself inferior and smaller lives which help to build it up, even as man gathers into his body these inferior and smaller lives which help to make that body; and partly by the outflowing from its own core of subordinate lives. Each such world thus takes a form and a quality and a substance which is a mass of atoms expressing the inner forces of itself. It thus manifests a spiritual or energic side, and a material or vegetative or body side.

This course of progression of a monadic ray through the spheres, from higher to lower planes, is naught else but a succession of states, spiritual, ethereal, astral, physical, which follow each other continuously, each being a continuation on a lower plane in the descent from a preceding higher state. It is like a flow of water. Thus downwards, from its spiritual origin in any one life cycle, passing cyclically through various planes, it continues that flow of successions of states as it progresses forwards, until it reaches the lowest point of matter attainable in that life cycle; then it begins its ascent on its return to more ethereal realms, and finally to those realms which are its original source — spirituality.

At the end of its period of existence on any one plane — our own physical plane for example, which is its most material sphere, and therefore its turning point before it reascends — our universe, any universe, passes into the invisible realms when its life cycle is run in these realms of matter; even as man passes into the invisible realms when his life cycle is run on this earth. That particular life cycle is then ended. It has attained once again its primordial point of departure, but now it is greater, grander, because more evolved. And with it into invisibility have gone all the various organs or spheres or houses of life which composed the universe, each one with its manifold assortment of lives, which are incomputable in number, for there are hosts upon hosts, hierarchies upon hierarchies of them.

After a long, long period of universal repose, a definite time period called a pralaya, (1) our universe follows a new cycle down into newer substances and matters acting according to a preceding cause, which we may call an evolutionary seed, the fruitage of its former self. The vast aggregate of life forces which now reawaken into life again inform and comprise a nebula, the first manifestation of the stirrings of its own inner life force. Then, passing through various nebular stages of evolution, it will in time settle down anew into stellar and planetary bodies, each one of such bodies bringing forth anew what is within itself, its intrinsic and inherent and latent life forces, expressing itself on this plane, which is a somewhat higher one than the plane on or in which our universe in its preceding period of manvantara had manifested itself .

Yes, these worlds must have their period of repose, even as man must have his, when his cycle is run. When that period comes they rest in the invisible realms with all their freightage of lives, and after that rest return and repeat the cycle of evolutionary manifestation, but at each recurrence on higher planes than the preceding.

Nature repeats herself everywhere. She follows grooves of action that have already been made; she follows the line of least resistance in all cases and everywhere. And it is upon this repetitive action of our Great Mother — universal nature — that is founded the law of cycles, which is the enacting of things that have been before, although each such repetition, as said, is at each new manifestation on a higher plane and with a larger sweep or field of action. Back of all the seeming of nature, behind all the cyclical phenomenal appearances which our senses interpret to us as best they may, lies the universal life in its infinitude of modes of action and expression.

Let us now take another step in outlining this doctrine. What is it that causes this materialization or concretion or thickening of the original substance of a world or a universe? The answer is to be found in the teaching that spirit and essential substance are fundamentally one; which is virtually what the greatest scientific physicists believe when they declare that matter and force (or energy) are fundamentally one. This may seem like a dark saying and a hard one at first sight, but it is current scientific physics, thus reechoing the age-old philosophy.

At a certain stage of its movement forwards and downwards of progression or evolution, force passes the frontiers of any particular world-sphere and becomes very ethereal matter, because actually force is ethereal matter, so to say; or, to put it more accurately, matter is crystallized force.

Force is merely moving matter, or matter in movement, subtle matter, flowing matter. Force on the ethereal planes, or rather forces, are substances: on these ethereal planes they actually are solids, fluids and, if you like, "gaseous" matter; but in our more gross and material world, we sense them only as forces. Electricity is a case in point. It is material; we know that. Otherwise, indeed, how could it work in, through, and upon substance or matter, if it were entirely different from matter and had in itself nothing of a substantial nature? These forces working in the ethereal realms of matter are extremely subtle.

Spirit and substance are fundamentally one. Matter passes into force or energy, or substance passes into spirit, when the material or substantial cycle of either is completed — that is to say, when the cycle of any particular evolving entity, be it globe or anything else, is ended, when its time of dissolution or vanishing again into the invisible world arrives. Matter is thus metamorphosed into force again.

The English physicist, Sir Oliver Lodge, stated in a lecture a number of years ago, that the universe is composed of something which he called "substantial," but which we cannot as yet understand; yet this "something" is an old story in the age-old philosophy. Theosophists call this something "substantial" one of the garments of mūlaprakṛiti ("root-matter"), that garment being the ākāśa, a Sanskrit term meaning "luminous" or "brilliant." The primordial or original physical matter of which Sir Oliver speaks is the lowest or most material form of ākāśa — and perhaps we might call it "ether," though there are many cosmic ethers of many grades of tenuity, ranging from the lowest material through all intermediate stages to the most highly spiritual.

This teaching of the ultimate identity of force and matter, or spirit and substance, is important because, among other things, it furnishes a perfect encyclopedia of suggestions from which to draw conclusions about these vexing problems. But in talking of these things we find that language is inadequate. We in the West have no terms by which to express these utterly new thoughts. We see matter moved by force or energy, and when we examine it more particularly we find that matter is really matters, and that force is really forces.

Now what are these forces? They are monads which have reached full development for and in our own particular hierarchy, that is, our cosmical system, both inner and outer; and that it is their life-impulses, their vitality, which furnish the energies with which the cosmos manifests. More simply put, the forces of the cosmos that we know are the life-impulses, the will-impulses, of these fully developed monads of our hierarchy. In ancient times they would have been called gods, modern scientific thinkers call them forces; but the terms really matter nothing.

The universe is composed of units, and the heart or core of each one of such units is what we call a monad. Each of these monads is a spiritual consciousness-life-center. As the universe is infinite, and comprises infinite stages or steps, so these stages or steps are formed of the incomputable hosts of monads in various degrees of self-expression; or to put it more accurately, are composed of the vehicles or bodies in which each such monad manifests itself as in a garment taken from its own life and substance. Such is force and matter. Yet the forces which play in and through the cosmos, although themselves substantial, seem unsubstantial and immaterial to the lower parts of the cosmos in which they all work. Seemingly illusory for us, we do not understand them as they are in themselves.

Consciousness, therefore, is matter too; matter is consciousness; for the cosmos is composed of nothing but an infinite number of spiritual entities, "spiritual atoms," if we like, self-motivated, self-driven, self-impelled particles of consciousness.

When an automobile speeds along the road, it carries with it everything of which it is composed. And so is it with the various bodies or "vehicles" which enshrine and manifest and express the indwelling powers or energies or forces, whether such body or vehicle be a sun or a planet or a comet or a human body, or an animal body, or any other body. The directing intelligence sitting at the wheel is representative of the directing intelligence sitting at the heart or core of each and every manifesting body in the cosmos. This directing intelligence is the divine hierarch of the hierarchy or cosmos, great or small, which it guides and inspirits. The same law runs throughout the countless hierarchies which make up the whole universe as a composite entity. Man's body, for instance, is composed of innumerable lives, hierarchies of lives, of various grades; and ruling over these sits man himself in the temple of his soul, the directing intelligence of all. Man is a composite hierarchy.

These teachings of the inner nature of force and matter explain the process by which all hierarchies pass through their evolutionary life cycles. The spiritual body of the universe in its inception becomes more material as the substances and energies of which it is composed transform themselves into inferior matter. The coarsening of these forces proceeds apace as the universe runs its course down into what become material realms.

When the materialization has reached its ultimate, or to put it more clearly, when such materialization has reached what for any particular universe is its period of densest physical existence, then such coarsening or materialization stops, and this is the turning point in the evolutionary path of such a universe. There ensues a change in the direction, as it were, that the universe henceforth must follow. Matter begins then to etherealize itself, to reenergize itself, to rebecome energy, but very, very slowly of course. It takes aeons upon aeons for this cosmic work to eventuate in evolutionary perfection; but that work goes on all the time, without intermission and without ceasing at any instant. Therefore, as this etherealization goes on, as this re-etherealizing of the matter of which the universe consists proceeds, that universe rebecomes the forces of which it was at first composite, but with all the added qualities and characteristics of an evolved cosmic entity; and this takes place on a higher plane than that which witnessed the evolution of the universe that preceded it.

The passing of matter back into force gradually leads it upward and upward through progressive etherealization and final spiritualization, until ultimately it rebecomes spirit in those cosmic realms whence it originally set forth on its long evolutionary cyclical journey; but greater in quality and of superior texture in all senses is it when it returns to that primordial source. It is these two procedures that take place during the passage of a world from the invisible into the visible, and then from the visible back into the invisible.

1. The periods of evolutional activity are called in theosophy manvantaras, a Sanskrit term which means periods of manifestation when the universe is not "asleep." In the periods of rest or of "sleep" it reposes. These latter are called pralayas, another Sanskrit word, meaning "dissolution." Yet if we were to analyze these periods of rest we should find that they are not a state of mere "nothingness" but are made up of condition after condition through a complete cycle, which closes only as the new cycle of activity begins. (return to text)

Man is a mystery, a mystery to the investigating mind of the researcher into nature; but more so indeed is man a mystery to himself. Yet there is a solution of this mystery — a solution which is not new, which is older than the enduring hills. Man, child of the universe, nursling of destiny, stands between two immense universes, between the vast sphere of cosmos and the atom of physical matter — one of cosmical, the other of infinitesimal magnitude. It is on account of his having attained this present stage in his long evolutionary journey that he so conceives of himself as holding this intermediate point, and from these two universes he draws the life-springs of understanding which dignify him as man. Yet the majestic philosophy-science-religion of the ages teaches us that there are beings so much greater and higher than man is, and beings so much smaller and less than he, that in reality he himself in turn stands in his world and cosmos as the one or the other of these extremes to such greater or smaller entities.

It is a question of relativity. In order to understand it more clearly we must cleanse our minds of old ideas instilled into us by false education, both religious and scientific, and philosophic too; also must we understand that man's is not the only mind which can conceive universal things, and that our status in the cosmos is not the only one of supreme importance, as we foolishly but perhaps naturally imagine it to be.

Universal life is infinite in its manifestation in endless forms, and manifested beings are incomputable in number; and no one may say that man, noble thinker as he truly is, is yet the only one in the boundless fields of space who can think clearly and imagine rightly and intuit truth. Such egoistic notions of our uniqueness in the scheme of life are really a form of insanity; but the mere fact that we can understand this egoism and struggle against it, shows that we ourselves are not insane.

Therefore, since both in the very small and in the very great, consciousnesses exist and fill all space, we are their children, their evolving offspring. Moreover, insofar as the small universe is concerned, the microcosm, within certain frontiers we as individuals are likewise parents of offspring occupying to us the same relative position that we occupy to those greater consciousnesses.

Biologists today compute that in the body of man there are some fifty trillion cells, more or less — living things, physiological engines — out of which his body is built. These cells in their turn are composed of chemical molecules, which in their turn are composed of atoms; and these atoms in their turn are composed of things still smaller, today called protons, neutrons, and electrons; and for all we may know, these subatomic particles, supposed to be the ultimate particles of matter, are themselves divisible and composed of entities still more minute. Is this the end, the finish, the jumping-off place? Are there particles still smaller than these? If we are to judge by the past, we are driven to suppose that there is no end.

Where dare one say that consciousness ends or begins? Is it of such a nature that we must suppose that it has a beginning, or reaches an end? If so, what is there beyond it, above it, or below it? If consciousness of any kind, man's or any other, have a true limit in itself, then the power of our understanding would not be what it is even in our present relatively-undeveloped stage of evolution. We could have no intellectual or spiritual reaches into these wider fields of thought.

We sense something of limitations along these lines in our ordinary brain-functioning, because our brain is in itself limited; but every thinking individual, if he examine himself carefully and study his own experiences, must realize that there resides in him something which is boundless, something which he has never fathomed, which tells him always, "Come up higher. Reach farther and farther into the beyond. Cast all that has a limit aside, for limits do not belong to your higher self." This consciousness is the working in man of the spiritual self, the operation in his psychological nature of his spiritual monad, the ultimate for him in this our hierarchy of nature only, for that spiritual monad is the center of his being, and in itself knows no limits, no boundaries, no frontiers, for it is pure consciousness.

Evolution — the drive to betterment. If we look at it as a selfish materialist, then it means superiority over our fellowman for our own advantage; but if we look at it according to the instincts of our own being, it then means self-superiority in the sense of rising on the ladder of life ever higher, with expanding vision, with expanding faculties and sympathies — growing greater from the spiritual core of our being. In other words, it means opening up for that spiritual essence within us wider doors for it to pass its rays through, down into our personal minds, enlightening and leading us upwards and onwards, illimitably through the various cosmical periods and fields of evolution which the monad follows along the courses of destiny.

Man, as one of the spiritual-psychical-physical corpuscles in the living cosmos — as the microcosm of the macrocosm — merely follows the same operations of nature that the cosmos is impulsed, compelled, to follow: development, growth from within outwards, throwing outwards into manifestation as organic activity, as expression in organs, so far as his physical body is concerned, the functions, the impulses within, the drive, the urge to manifest what is within. That, in a few words, is the ancient teaching of evolution.

Now let us take up the question of the evolution of animate beings on this earth more definitely from the theosophical standpoint. We use the word strictly in its etymological sense, as an unwrapping, an unrolling, or a coming out of that which previously had been inwrapped or inrolled. Nor do we mean by evolution the mere adding of physiological or morphological detail to other similar details, or of variation to variation or, on the mental plane, of mere experience to other mere experiences; which would be, as it were, nothing but a putting of bricks upon an inchoate and shapeless pile of other bricks.

No, evolution is the manifestation of the inherent powers and forces of evolving entities, be those entities what they may: gods, or humans, or other animate entities below the human. It is a coming forth of that which formerly had been involved or inwrapped. It is the striving of the innate, of the invisible, to express itself in the manifested world commonly called the visible world. It is the drive of the inner entity to express itself outwardly. It is a breaking down of barriers in order to permit that self-expression; the opening of doors, as it were, into temples still more vast of knowledge and wisdom than those in which the entity previously had learned certain lessons. It is this rather than any mere adding of detail to detail, of variation to variation. Evolution is a cosmical, a universal, movement to betterment.

All entities that infill space are following a path to higher things, all are delivering themselves of that which is locked up within them. All are pouring forth the myriad-form lives which they contain — their inner selves and their thought-forms — their vehicles slavishly following the courses that these entities run. Contrast with this conception the encyclopedia definition of evolution as a "natural history of the cosmos including organic beings, expressed in physical terms as a mechanical process."

The theosophist rejects that definition; first, because it leaves out the main characteristic of evolution, which is unfolding from the less to the greater; it says nothing of development towards higher things. Second, it is a merely mechanical and purely theoretical explanation of things that should be considered by the different sciences in their own various departments, and it expresses no unification of those sciences or does so only in terms of dead matter, formed of atoms — driven together by fortuitous action.

The main thought is that at the core or heart of every animate entity, there is a power, an energy, a principle of self-growth, which needs but the proper environment to bring forth all that is in it. You may plant a seed in the ground, and unless it has its due amount of water and sunshine, it will die. But give it what it needs, let it have the proper environment, and it brings forth its flower and its fruit, which produce others of its own kind. It brings out that which is within it. Yet environment alone cannot produce the flower. There must be an intelligent entity to act upon environment.

Thus man, the evolving monad, the inner, spiritual entity, acts upon nature, acts upon environment, upon surroundings and circumstances, which automatically react, strongly or weakly as the case may be. Environment in a sense is an evolutionary stimulus, allowing the expression, as far as its influences can reach, of the latent powers of the entity within the physical body. Herein we find the true secret of evolution.

True evolution is the unfolding and flowing forth of that which is sleeping or latent as seed or as faculty in the entity itself. This works along three lines which are coincident, contemporaneous, and fully connected in all ways: an evolution of the spiritual nature of the developing creature taking place on spiritual planes; an evolution of the intermediate nature of the creature (in man the psychomental part of his constitution); and a vital-astral-physical evolution, resulting in a body or vehicle increasingly fit for the expression of the powers appearing or unfolding in the intermediate and spiritual parts of the developing entity.

Hence, the theosophist of necessity considers the destiny and evolution of the inner parts of the being as by far the most important, because the evolution or perfecting of the physical body has no other purpose or end than to provide a vehicle, progressively more fit to express adequately the powers of the inner nature. Evolution is thus the drive or effort of the inner entity to express itself in vehicles growing gradually and continuously and steadily fitter and fitter for it.

William Bateson, a British biologist, expressed the idea by calling it the "unpacking of an original complex." Turn to a flower or to the seed of a tree. The flower unfolds from its bud and finally attains its bloom, charming both by its beauty and perfume; we see here the unwrapping of what was latent in the seed, later in the bud, later in the bloom. Or again, take the seed of a tree: an acorn contains in itself all the potentialities of the oak which it will finally produce — the root-system, the trunk, branches and leaves, and the numerous fruits, other acorns, which is its destiny finally to produce, and which in their turn will produce other oaks.

Evolution is one of the oldest doctrines that man has ever evolved; because evolution properly described is merely a formulated expression of the operations of the cosmos. But this ancient doctrine of evolution is not the evolution of modern science, either in its view of man or of the cosmos. What then is the so-called evolutionism so popular today? It is really "transformism" — an adopted French word. So what is the difference between this and the theosophical doctrine of evolution?

Reduced to simple language, transformism is the doctrine that an unintelligent, dead, nonvitalized, unimpulsed cosmos, whose particles are driven hither and yon by haphazard chance, can collect itself into the forms of innumerable sub-bodies, not only on our earth, but everywhere else, these sub-bodies on our earth being called animate entities, all of which grow to nobler things, how no one knows, therefore no one can say. It is a theory, an hypothesis. It is, in short, the doctrine that things grow into other things unguided by either innate purpose or inner urge.

How can a haphazard, helter-skelter universe produce law and order, and follow direction, and suffer consequences, results strictly following causes? We reject the idea because it is unphilosophical and unscientific. Theosophists are evolutionists but not transformists. The idea that one thing can be transformed by random changes into another thing is like saying "give me a pile of material — so much wire, so much wood, so much ivory, so much varnish, and a few other things — and just watch that pile evolve into a piano!"

There is an old Qabbalistic axiom which runs as follows: "The stone becomes a plant; the plant a animal; the animal a man; and the man a god." So it is; but the literal form of these words should not be construed as expressing a perfect Darwinism; not at all.

First, the allusion is to the monad expressing itself through its lowest vehicle, not living in it, but overruling it, working through it, sending a ray down into its lowest body, in this case the "stone." The monad provides the invigorating life force, giving to the stone, which is composed of other hosts of infinitesimals, its vital ray. When it is said that the stone becomes a plant, it means that the infinitesimal entities forming and composing the stone have been evolved to express that invigorating ray on a higher plane as a plant; but the inner life and illumination of the monad directing the whole procedure as a unity never abandons its own high plane.

When the plant becomes an animal, the vehicle expressing the invigorating ray from the monad has become fit for that still higher work. The infinitesimal entities forming the plant have become still more evolved or more expressive of the vital ray, and when this occurs they compose and form the animal body, having passed beyond the stage of expressing the plant or the stone.

When the animal becomes a man, it does not imply that man sprang from the animals, whether from apes or monkeys, or beneath these from the lower mammals. No; it means two things: first, that the inner sun, the inspiriting and invigorating monad — abiding always in its own sphere, but sending its ray, its luminousness, down into matter — thereby gives matter kinetic life and the upward urge, and in this way builds for itself ever fitter vehicles through which to express itself. And second, that each such fitter vehicle was built up by and through the infinitesimal lives which at one period of their existence had lived previously in the animal body which they composed; and before this in the plant which they composed; and before this in the stone which they composed; and lower than the stone these infinitesimal lives manifested the monad in the three worlds of the elementals.

The idea of this progressive development from within outwards is easy to understand in principle. We do not teach that a stone literally metamorphoses itself into a plant and then into a animal at some specified time. Or again, from an animal to a man; or from a man into a god.

The physical body, an aggregate of living infinitesimals, itself never becomes a god. It is a transitory aggregate; in reality a form and a name and nothing more — the nāma-rūpa of Hindu philosophy. But these infinitesimals which compose the body, being growing and learning and advancing lives, grow ever more fit to express the nobler faculties of the genius overruling and illuminating them, and thus pass by what the ancients called metempsychosis (1) into the composition of the bodies of the respective higher stages. That genius, in the case of the infinitesimals composing man's body, is man's spiritual nature, for genius and monad are virtually equivalent in the meaning I am using here.

Compare this logical and comprehensive doctrine with the scientific hypothesis of transformism: i.e., that, following various supposed "laws of nature" operating in individuals, one body is transformed into another. Thus stones will transform into trees, trees into animals, and animals into men. Biological scientists do not put it in that fashion, but it illustrates the precise meaning of the word transformism.

Charles Darwin, for instance, argued that man evolved from the animal kingdom by small, successive modifications, that is, random variations favored by natural selection, resulting in the survival of the fittest in their particular environment. His ideas were partly based in but generally superseded the speculations — some of them exceedingly fine — of the Frenchman, Lamarck, who taught what has since been called the theory of acquired or favorable characteristics; that is to say, that an animate entity, by acting upon nature and from the reaction of surrounding natural entities and laws upon it, acquired certain favorable characteristics, which were inherited and passed on to the offspring. As these characteristics were always for the betterment of the individual acquiring them, therefore there was a gradual advance and progress of that particular racial strain. Let me illustrate this idea of acquired or favorable characteristics by a bit of old doggerel:

A deer had a neck that was longer by half

Than the rest of his family's (try not to laugh),

And by stretching and stretching became a giraffe,

Which nobody can deny!

But both theosophists and Darwinists deny it. If we inquire into the nature of elongate-necked deer, we shall most certainly find that their offspring are perfectly normal. Acquired characteristics by an individual are known not to be transmitted by physical heredity. Individuals of course are tremendously affected by environment and circumstance, by their action upon nature and by the reaction of nature upon them; and through long periods of geologic time it is probably true to say that the body of the acting individual, or succession of individuals, would slowly acquire specific modifications. But this would invariably be along the lines of functional tendencies or capacities inherent in the genes. But if all the representatives of any particular phylum live and die through long generations in some particular environment, do they or do they not acquire characteristics or modifications which become so much a part of their physical being that these modifications are transmitted by heredity? This is precisely the question so warmly disputed.

While evolution is a fact, the main question is whether the fortuitous action through long periods of time of individuals upon nature, and nature's fortuitous reactions upon those individuals, suffice adequately to explain the process. The idea is steadily growing more and more unfashionable, because the problems of the origination and growth of self-consciousness, and of intellectual development, are inexplicable by it. The real question at issue is this: is there not behind the evolving human race, as expressed in its individuals, a vital urge or drive to betterment, working from within outwards? If so, it is true evolution. If the materialistic transformist denies this fact, he has the tremendous onus probandi before him, the almost insurmountable difficulty of explaining whence and why and how these marvelous faculties arise and increase in power and expression with the passage of time. No transformist has yet succeeded in meeting this issue.

The Darwinists talk of the struggle for life, but we claim that this so-called struggle has been greatly overdrawn. It has now become quite popular to believe on proved facts that there is just as much mutual assistance and helpfulness in the animate portion of the cosmos as there is combat and struggle; indeed, more. Do we deny, then, that natural selection, the struggle for life and the survival of the fittest are factors in evolution? The simple answer is no. There is nothing new whatsoever about that idea.

The theosophical philosophy-science-religion is based on nature; not alone on the material physical nature which we know with our physical senses, but on that greater nature, of which the physical nature is actually but the vehicle, the expression, of indwelling forces. By nature we mean the entire framework and course of the cosmos, from the ultraspiritual down to the ultraphysical — limitless in each direction. From all the above we can see that to the theosophist evolution extends over far wider fields, and reaches to far greater heights, and we observe it operative in nature in a far more complex manner, than does the relatively simple teaching of modern scientific transformism.

1. See Chapter 10, "Reincarnation and Evolution," for a fuller explanation of the term metempsychosis; see also the author's work, The Esoteric Tradition, where the subject of reimbodiment in its several forms is treated in depth. (return to text)

The psychology of the times following the publication of Darwin's works was so strong that most thinking men could not then be brought to admit that there were any alternative explanations of the phenomena of progressive development in life — human, animal, or plant life — to the scheme of transformism which he set forth. This psychological phenomenon was brought about mainly by the efforts of two men, men of large culture, but vociferously enthusiastic and more or less dogmatic in the presentation of their views; and they ended by convincing the world that the evolutionism, in reality the transformism, that they taught was the actual procedure of manifested life in producing development in all creatures.

These two men were Thomas Henry Huxley and Ernst Heinrich Haeckel. Both were fervent Darwinists. Their influence, on the whole, has not been good upon the mentality of the human race. We do not question the bona fides of either of them, but we do question their influence for good upon thinking and unthinking minds. They taught things that in many important essentials were not true, and taught them in such fashion that their hearers were led to believe that they were true. This influence was brought to bear upon the minds of the people of those days by means of the great literary and scientific standing which these two men in particular had. These two men were exceedingly able; but they spoke with the voice of authority on subjects which they themselves, in many particulars, were merely guessing at. These conclusions are not mine alone. They are also the conclusions of many scientific researchers and thinkers of today.

Take, as an instance, Haeckel. In our sense he was the more dangerous of the two, for the reason that he had a vein of mysticism running through him; and when a peculiar type of mysticism is combined with blind, crass materialism, it inevitably produces certain doctrines which actually degrade psychologically those who hear and follow them. A man who will say that there is nothing but intrinsically lifeless matter in the universe, striving chance-like towards better things; and who in the same breath will talk of "plastidular souls" — the "souls" of cells — these "souls" being explained apparently as the fortuitous offspring of lifeless matter; and who will, in order to complete his schemes of genealogical trees as regards man's developmental past, invent, suggest, and print imaginary stages of development in his books without also calling attention to the fact that they were his own inventions, is not, we submit, truly scientific.

One of these inventions is to be found in Haeckel's book, The Last Link, published in 1898. In it he divides the evolutionary history of mankind into twenty-six stages. His twentieth stage he gives as that of the "Lemuravida" (who were placental mammals), which might be translated from its hybrid Latin form as "the grandfathers of the lemurs" — the lemurs being a very primitive type of mammal, supposed to antedate the monkeys in evolutionary time, and often called Prosimiae (Prosimians). Now, no one ever heard of these particular "Lemuravida" before, and they have never been found since; and, as Professor Frederic Wood Jones, the British anatomist said, they were simply "invented by Haeckel for the purpose of filling in a gap." (The Problem of Man's Ancestry, pp. 19-20.)

Huxley was a man of very similar scientific type of mind, but with another psychological bent to his genius. He was psychologized with the idea that there was an end-on or continuous or uniserial evolution in the developmental history of animate beings; that is, that one type led to another type — the highest of the lower order or family or group passed by degrees into the lowest of the next following or higher group. His whole lifework was based on this theory; and all his teachings — backed by much biological research and anatomical knowledge, and other factors that make a man's words carry weight — had immense vogue for these reasons.

With this viewpoint in mind, he was continually trying to find connecting links by considering likenesses between man, for instance, and the various stocks inferior to him (1); and it must be admitted that in his attempt a great many unlikenesses and dissimilarities and fundamental differences, all of extreme importance, were either ignored entirely, or — may I say it? — willfully slurred over. It was the old, old story, both in Huxley's case and in Haeckel's: what was good for their theories was accepted and pressed home to the limit; and what was contrary to their theories was either ignored or suppressed. We submit that, great as these men were each in his own field, such a procedure is not a truly scientific one. We can excuse their enthusiasm; but an excuse is not by any means an extension of sympathy to the mistake.

The idea which governed and directed the entire lifework of Huxley was not the offspring of his own mind. There is little doubt that he was influenced by the Frenchman, de Buffon, who said, for instance, in speaking of the body of the orangutan, that "he differs less from man than he does from other animals which are still called apes" (Histoire naturelle, vol. xiv, p. 30, 1766; quoted by F. Wood Jones, op. cit., p. 21). And Huxley in 1863 wrote the following in Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature:

[T]he structural differences which separate Man from the Gorilla and the Chimpanzee are not so great as those which separate the Gorilla from the lower apes [i.e. monkeys]. — p. 123

Please note that I refer to end-on or continuous or uniserial evolution only insofar as Huxley thought it existed in the subhuman beings and their progenitors that he knew or thought must exist in order to conform with his theory. As a matter of fact, end-on, continuous, or uniserial evolution per se, is also fully taught by theosophy, but not in the particular line or course which Huxley took for granted: that is, that the beings below man formed or provided the evolutionary road eventuating in modern man.

This the theosophist emphatically denies, for the reason that the ancestors of the simian, and of other mammalian entities now existing, were themselves stocks following their own line of development, even as the human stock now does and then did. In other words, instead of there being one single line representing the ascending scale of evolutionary development passing through the geological progenitors of present-day mammals, towards and into man, there are several, and indeed perhaps many, such genealogical trees.

The theosophical teaching in brief is this: the human stock represents one genealogical tree, the Simiidae another stock, each following its own line of evolution. Yet the latter, the simian stock, originally sprang from the human strain in far past geologic times, and also, indeed, the other genealogical trees of the still lower mammalia; while the classes of the Aves or birds, the Reptilia or reptiles, the Amphibia or amphibians, and the Pisces or fishes, may likewise truly be said to have been in geologic times still more remote, very primitive offsprings from the same prehuman (or man) stock.

Huxley thus assumed, because there are undisputed and indisputable likenesses between man and the anthropoid or manlike ape and the monkeys still lower than the ape, that therefore man sprang at some remote period in the geologic past from some remote (but totally unknown) ancestor of monkey and ape. He had never seen such a missing progenitor, but he deemed that there must be one because it was necessary for his theory; and he so taught it, and taught it with emphasis and with enthusiasm. His voice rang out over the entire English-speaking world, and his ideas were accepted as established facts in organized knowledge — science.

We must not imagine for a moment that the natural truth of progressive development, modernly called evolution, is something new in our age or in the age of our immediate fathers, nor that it originated in the mind of Charles Darwin, whose great work, The Origin of Species, was published in 1859. The Qabbalistic axiom cited in the previous chapter is but one example.

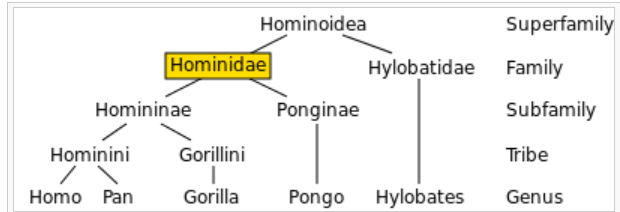

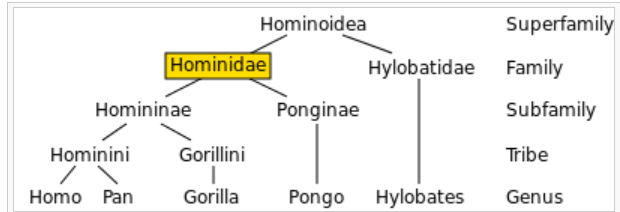

The idea of there being a ladder of life, a rising scale of entities, some much more advanced than others, some more retarded in development than others, is also a very old one. There have existed in the world among the different races of men, in ages preceding our own, various systems accounting for what man plainly saw among the animate entities of earth — a rising scale of beings: First man, supposed to be the crowning glory of the evolutionary scale on earth; and underneath him the anthropoid apes, and underneath them in descending order the monkeys, lemurs, and quadrupedal mammals; and underneath these, various classes, orders, genera, and species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals; and so forth down the scale.

This idea of a progressive development of all animate entities on earth in present and past geological periods is, indeed, a very old one. Leaving aside for the time being allusions to teachings as to evolutionary development in the archaic writings, such as in the Pūraṇas of India, or in the so-called speculations of Greek and Roman philosophers and thinkers, let us come down to periods more near our own.

For instance, Sir Thomas Browne's Religio Medici — quite a remarkable book of its kind and published in 1643 — says:

. . . there is in this Universe a Stair, or manifest Scale, of creatures, rising not disorderly, or in confusion, but with a comely method and proportion.

Just so. There is a stair of life, what the Swiss philosopher and biologist, Charles Bonnet, and the French thinkers and biologists, Lamarck, de Buffon, and especially Jean Baptiste Réné Robinet, called l'échelle des êtres — "the ladder of beings." It was the very recognition of this scale of animate life, swaying the minds of these earlier investigators, that led to the culmination in our time of the theory of evolution; and it was Charles Darwin who is responsible for having formed a more or less coherent structure of argument, building up a logical outline, as far as he could understand it, of the facts of nature — his theory explaining the method or process of change attaining almost immediate acceptance.

While we see this ladder of being, and must take it into a full and proper consideration in any attempt to ascertain the rising pathway of evolutionary development, is that a sufficient reason for imagining — and teaching these imaginings as facts of nature — that there has been a progressive development running through these particular and especial discontinuous phyla or stocks, and eventuating in man?

This is one side of our quarrel with modern transformism. The series is obviously discontinuous; none of the steps of this ladder melts into the next higher one, or inversely into the next lower, by imperceptible gradations, as should be the case if the transformist theory were true. Biologists themselves soon found that this so-called stair or ladder of life was discontinuous. As their knowledge of nature increased, they saw that none of these great groups — invertebrates or vertebrates or the classes within them — graduated into each other.

Between these various groups there were vast hiatuses without known connecting links; and researchers hunted long and vainly for "missing links," and found them not. They found them neither in any living entities, nor in those forming the formerly animate record of the geological strata; and those missing links have not yet been discovered. These gaps, therefore, made the biological series of living entities discontinuous instead of continuous, as Darwin's method requires.

Darwin and his followers imagined that they had perceived, by investigating various stages in this presently existing ladder of life, the route to present-day man. But every attempt to find missing links — that is to say, links binding the highest of one particular phylum or stock to the lowest of the next superior phylum or stock — has always broken down. There are wide hiatuses where, according to the transformist theory, these missing links should be. One of Darwin's maxims was Natura non facit saltum, "Nature makes no leaps" — which by the way is exactly what theosophists assert. Evolution is a steady progression forwards, he said, from the less to the more perfect, from the simpler to the more complex. There is here no ground for dispute between our two otherwise extremely diverse views as to the nature and course of evolution.

What then is the explanation of this discontinuity — of this lack of connecting links between the phyla or stocks? For we find this discontinuity in every instance where we pass from one great stock or phylum to the next. It is not the case of a single instance; it is not a unique situation, explainable perhaps by certain causes, of which we are ignorant; but this discontinuity is repeated between every one of the great stocks.

The fact is that there is not, as regards the beings existent today, or rather as regards their progenitors in geological eras of the past, an end-on evolution or uniserial evolution up to and including man, the supposed crown of that biological series, in the manner that we have been taught. Instead, there are a number of discontinuous stocks, each passing through various stages as marked out by their different orders and families and genera and species. Research has shown that instead of the highest of any subphylum passing into the lowest of any higher subphylum, it is almost invariably the lowest or oldest representatives of each phylum which are most alike in primitive features. It is so with all the groups, particularly so in the case of the vertebrates or animals with backbones, that is to say the fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.

The simple reason is that the farther we go back in time, the nearer we approach the junction point or starting point of the various mammalian (or, for that matter, premammalian) genealogical strains. In other words, the farther we go back towards the origin of any such mammalian group, the nearer we approach to the general and common point of departure — and the nearer those earliest progenitors of each such great group will resemble each other in basal mammalian simplicity. On the other hand, the farther or later we recede from that common point of departure, in other words, the nearer we approach our present age, the more widely separate the representatives of these various great stocks are from each other, on account of the differing natures and the inherent forces evolving through them.

What is this common point of departure? It is the human stock. The human race considered as a whole is the most primitive of all the mammalian stocks on earth today, and always has been so in past time. I mean by this, that it is the primordial stock; it is the originator of the entire mammalian line, in a manner and according to laws of nature which we shall reserve for a future study. The human stock was the first mammalian line; obviously it is at present the most advanced, and the logical deduction would be that it is likewise the oldest in development. Having started first, it has gone the farthest along the path. But we will not press that point for the present.

Man is, in fact, the most primitive of all stocks on earth. Remember, however, that in the present great evolutionary period on earth, or what in theosophy is called the present "globe-round," it is the mammals only that trace their origin from the primitive human line.(2) The other vertebrates, as well as the great groups of the invertebrates, likewise were derived from the "human" stocks, but in the previous globe-round — comprising a vastly long cycle of evolutionary development, which was ended aeons upon aeons ago, and which itself, i.e., the former globe-round or great tidal wave of life, required scores of millions of years for its completion. Evolution as taught by theosophy calls for a time of vastly long duration; indeed, many hundreds of millions of years.

The Darwinists have never been able adequately to prove the thesis of Charles Darwin, considered as the mechanism or method of evolution, because they could not prove an end-on, continuous, or serial developmental growth from any one of the lower great groups into the next higher great group; or, more generally speaking, from the lowest life up to man. There is along that scale, let me repeat, no end-on evolution, and none knows this better than modern biologists themselves.

Yet theosophy teaches that evolution must be an end-on, continuous, or uninterrupted serial evolution. An evolution of form which consists mainly of jumps from great group to great group is no evolution at all, and presents anew the very riddle which the Darwinian theory was expected to explain. The problem is cleared up when we remember that evolution is continuous for each stock along its own particular pathway. Instead of there being one ladder of life, leading up to man who is the crown of that ladder, as it were, there are many such ladders of life, each such being composed of one of the great groups of animate entities. Instead of there being one procession of living entities pursuing an uninterrupted course from the protozoa or one-celled animals up to man, there are various ladders of life along each of which a procession of its own kind climbs. It is essential to understand this idea, because it expresses some of our main points of divergence from the Darwinian theories.

1. [Throughout this book the author's generic use of the term "stock" may refer to any biological group, from phylum to species.] (return to text)

2. [See "The Rounds and Their Subdivisions" in Appendix 1]. (return to text)

"Man is his own history." This is a profound epigram which covers the entire outline of the evolutionary progress of the human soul. All things reside in man. He is the epitome of all that is — the microcosm or replica, the duplicate, the copy, of the macrocosm. Therefore he has everything in him that the macrocosm has, although not necessarily fully developed. On the contrary, many of the higher forces, qualities, potentialities, as yet but very feebly show through the veils which enshroud his higher nature; nevertheless he possesses all the elements that his Great Mother — the universe — has, either latent or sleeping, or expressing themselves through his self-conscious side.

Man also holds within himself the history of all inferior types. Man is, and has been, and will be, the foremost of the hierarchy of evolving entities on our earth, the foremost in evolutionary development; and as the leading stock, he therefore is the repertory, the storehouse, the magazine, of all future types, even as he has been of all past types. He throws off these types as he evolves through the ages; each of them becomes in its turn a new stock, and follows thereafter its own individual line of evolutionary development.

It was in this manner that were originated all the stocks below man. Every inferior or subordinate stock was originated as the vital off-throwings of man, these off-throwings being composed of cells of man's body. And each one of these cellular organisms, succeeding its derivation or independent origin from the human stock, immediately began to produce its own stock from the forces inherent and latent in the cells which composed it.

It was these buds, these cellular off-throwings of man from his body, which originated all the stocks below the mammalia in the preceding globe-round or great tidal wave of life, hundreds of millions of years ago. Those particular classes were the birds, the reptiles, the amphibians, the fishes, and the vast range of biological life included under the general term of the invertebrates.

The mammalia, however, were the off-throwings from man in the present great globe-round or great tidal wave of life, and had their origin from prehuman man in the very early part of the Mesozoic, and very probably in the last part of the preceding or Paleozoic era, when man himself had become a physical from a semi-astral being.(1)

I do not mean by what I have said above that these types were or are the bodies in which man once lived, or will live. Not at all. The whole matter of the vital off-throwings is a fascinating and mysterious one, mysterious simply because not yet fully understood.

The human body is an exceedingly absorbing subject in any consideration of the manner in which evolution works. Physical evolution deals with it but in a secondary or effectual manner, not in a primary or causal manner. I mean by this that the human body merely reflects the various changes in progressive development which actually proceed on interior or causal planes. I have already pointed out that evolution, as we use the word, means the unfolding, the unwrapping, of that which previously had been infolded and inwrapped as potencies in the structure of the cells of which the body is composed; for in the infinitesimal lie the seeds of the world we see about us.

Each cell is, in fact, a living entity, a physiological organ, with inherent capacities, inherent tendencies, each possessing its own inherent urge or drive towards self-expression. According to theosophy, this inherent urge or drive originates in the invisible entity from which it proceeds; because, unless there were some cohering power, some force of coherence working in the structure of the individual, no such thing as even a simple cell could exist; it could not even come into physical being or manifestation. It is held together and controlled by the invisible entity behind it, which expresses itself through the finer or more ethereal part of these tiny cells, because that finer or more ethereal part is the nearest in ethereality to its own nature.

A cell is, in fact, an infinitesimal focus of cosmic forces, a channel through which they pour forth into manifestation on our physical plane, each possessing an incomputable capacity for change and growth, being in very fact a dynamo of forces. The incarnating entity is a bundle of such forces and expresses itself through the finer or more ethereal part of the cells, because that finer part is the nearest in ethereality to the nature of the force or forces that are seeking expression.

These forces working in the ethereal realms of matter are extremely subtle; their rates of vibration are highly individual. Yet with all their subtlety they have tremendous power. Could such a force be focused directly, let us say, upon the outer physical cell, such a cell would vanish, because it would be disintegrated; the atoms of which the cell is composed could not stand the strain of the forces pouring through them, and the structure of the cell would be wrecked, the component parts of the atoms wrenched apart. But it is very rare indeed that a force is so focused in animate entities, although it does happen constantly and continuously in the cosmic labor. The operation of these ethereal substances which we know as forces is, as a rule, more generally diffused.

Now every cell in man's body is man's own child. Every one of the estimated fifty trillions of cells sprang from him, from his inner self. The dominating entity, the inner man, gave birth to them all. As common parent of them all and working through them, he is their "oversoul." He in a very true sense is their god, even as the divine beings who gave us spiritual birth we call our gods; and just as these divine beings in their turn sprang as spiritual atomic corpuscles from entities still more sublime, and so forth, still higher — an endless hierarchy of ascending and descending intelligences and lives.

It can be seen from the above that in a cell, or in the atoms of which a cell is composed, there are uncounted and actually almost innumerable possibilities of development, locked up or latent potentialities, all seeking expression. Many have to bide their time for ages before that opportunity comes, if their opportunities ever do come; and if and when these potentialities find in their environment an open door for expression, out they go, a rushing tide of life.

Therefore, the cells that man once threw off resulted in the lower creatures, who are not at all degenerate men, as might be supposed, but actually lower types, beginning their evolutionary course towards higher things, springing from man, the repertory or magazine of all types beneath him.

Let us remember that the physical encasements of early men were far more loosely coherent than they are now, and of a much more subtle and ethereal matter than that of man's present physical body. This was because the psychical and physical dominance of the human kind over the cells composing those primitive human bodies was far less strong and less developed than it is now. In consequence of this relatively weak control over the physical cells, each one of such cells was more free than now it is to pursue its own particular individual drive or urge.

Hence, when any one of the cells forming part of such early human bodies freed itself from the psychical and physical control that then existed, it was enabled to follow, and instinctively did follow, the path of self-expression. But in our days when the psychical and physical dominance of the human incarnated entity over the human cells composing the human body is so strong, and because the cells have largely lost their power of individual self-expression through the biological habit of subjecting to that overlordship of the human entity, such an individualized career of a cell in self-development is a virtual impossibility. However, in those early days of the primordial humanity, the case was very different. A cell or an aggregate of cells could separate itself from the then human frame — if "human" is the proper word to use in such connection — and begin an evolutionary career of its own. This in large degree explains the origin of the various stocks now inferior to the human.

Man has been the storehouse (and still is) from which these other stocks originated and towards which, moreover, they are ultimately straining — towards which they are ultimately evolving. These cells which compose his body, had they not been held in the grip of the forces flowing from the inner dominating entity, man himself, for so long a time that their own individual lives, as it were, have been overpowered and bent in his direction and can now follow almost no other path than his; had they not been so dominated they would, by the amputation of a limb for instance, immediately begin to proliferate along their own tendency-line, to build up bodies of their own kind, each one following out that particular line of life force, or progressive development, which each such cell would contain in its cellular structure as a dominant, thus establishing a new ancestral or genealogical tree.

What is the reason that today a free human cell or an amputated human limb or a bit of the human body cut off from the trunk does not grow into another human being or, perhaps, into some inferior entity, as was often the case in the zoological past? In all the vertebrate animals, that is to say, the higher animate beings in the evolutionary scale, the psychic and material grip of the dominant entity over the cells of its body is so strong that these cells obey the more powerful drive communicated to them from the dominant entity working through them, and hence can follow only that dominating drive which they do through the force of the acquired biological habit. They have largely lost the power of self-expression and self-progress along what would be under different circumstances their own individual pathways. But that liberty of action and that free field for self-expression were theirs in greater or less degree in past times.

In some of the lower creatures there exists today a faculty of self-repair by which a creature, if it lose a limb or a tail, will reproduce for itself a new limb or tail. A certain kind of worm well known to zoologists will, if divided into two, become two complete worms. Here is a case where the faculty of dominance, or the dominant as Mendel called it, is still weak in its control over the entire cellular structure of the body through which it works, and each cell composing that body, if left to itself — even more so if you could take such a cell out of the body and give it appropriate food and environment — would have an exceedingly good chance of starting upon a line of evolution of its own, following its own inherent tendency or potency or urge, and thus bringing forth some new stock. But as this case rarely now or perhaps never arises, the cells are impelled to follow the reproductive tendency of the limb only to which they belong.

This method of the regeneration of lost parts, or of reproduction, prevailed in a past time in the human frame, as much as and as fully as in the cases of the lower creatures to which I here allude. And it was this general method of reproduction which gave rise to the various animate stocks, the highly specialized descendants of which we find on earth today (except those stocks which have become extinct). But this cannot happen in our period of evolution. The cellular structure, the inherent tendencies or potencies of the cells belonging to the bodies of the higher creatures, have the possibility of following only that particular line of unfoldment or of growth which the dominant entity allows them to have.

It is a case where the individual svabhāva, i.e., the individual capacities or latent tendencies of the cell, are submerged by the overlording or dominance, so to say, of the invisible entity which works through those cells. The inherent potencies of those cells have become recessive, the consequence being that the cell's own individual potencies can express themselves, if at all, only when the power of the dominating entity is withdrawn, perhaps not even then if the submergence of the cell or native cellular potencies has been too great. In this last case they die.

Man still remains the storehouse of an incomputable number of vital or zoologic tendencies latent in the cells of his body; and though the old method of their manifestation has ceased, new and different methods will supersede the old. The urge of life working through the tiny lives of man's physical body will nonetheless inevitably find new methods of expression, and these latent or sleeping tendencies will in far distant future ages find appropriate outlets, thus, perhaps, giving origin to new stocks in that far-distant future. It should not be forgotten, however, that such originations of new stocks will grow fewer and fewer as time goes on towards the end of our globe-round, due to the growing dominance and ever-larger and wider exercise of the innate powers of the evolving human being, swamping and submerging all tendencies of a minor kind and of inferior biologicalenergy.

This fact that a cell or aggregate of cells is subjected to the dominance of an oversoul, the incarnating and incarnated entity, is simply the manifestation of what the theosophical teachings call the action of the law of acceleration and retardation, one of the subordinate lines, so to speak, of the general operation of karma or the law of consequences. This law of acceleration and retardation simply means this: when a thing occupies a place of authority in the evolutionary scale, or a position of dominant power over other and inferior or subordinate entities, through the operation of its own inherent forces, or indeed through the inertia of its physical being, no other entity under its sway can find a free field for self-expression while so placed. And every entity so constituted — or, what comes to the same thing, every other entity of which that dominating entity is composed — must obey the dominating urge, the dominating impulses of that overlord. The dominant entity pursues an accelerated course; while the inferior entities under its sway or composing its various parts are retarded in their individual courses of development, which they otherwise freely would follow.

I will give you a poor but perhaps graphic illustration of my meaning. When a railway train rushes along the rails, what does it carry with it? All the living entities in the various coaches, each one on its own errand, yet all for the time being helpless in the grip of the power to which they have subjected themselves. In somewhat similar manner the cells of the human body are subjected to the law of retardation in evolutionary development, so far as they are individually concerned, until the time comes when they shall have reached, through obedience to the dominating power, self-consciousness of their own, and thereafter grow into nobler learners and more individualized evolvers. Evolution is not merely an automatic response to external stimuli, but it is first of all action from within, unceasing attempts in self-expression; and each response to the external stimuli, which the natural environment provides, gives opportunity for a larger and fuller measure of self-expression.