SOLSTICES AND EQUINOXES

For most ancient peoples, the sky was compass, calendar, and clock. Throughout history, religious celebrations and sacred rites have been connected with one or another of the solstices and equinoxes. Christmas, for example, is associated with the winter solstice (a three-day period when the sun appears to "stand still" before commencing its northward journey). December 25 was celebrated by the ancient Mithraic religion as the birthday of its savior, also by the old Romans as natalis solis invicti — the "birthday of the unconquered sun." The Hopis of the American Southwest hold a winter solstice ceremony timed by their Sun Watchers. Its names mean "they come out" (Soya'la) — referring to the kachinas, the guardian cosmic spirits who protect and guide the Hopi through their seasons of life — and "the sun turns back" (Ta'wa A'hoyi), symbolizing the beginning and renewal of life and growth.

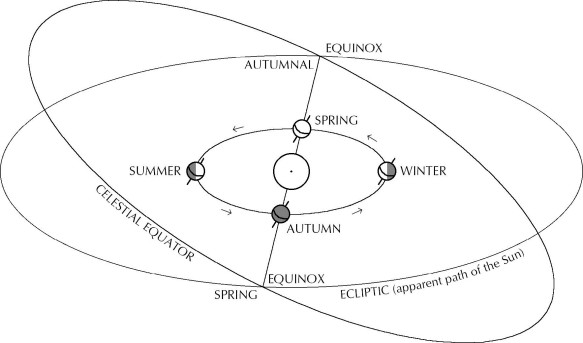

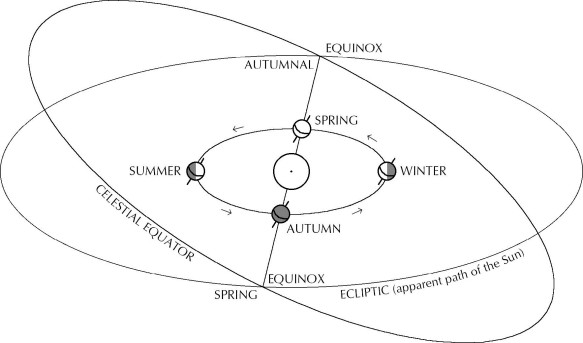

The equinoxes occur midway between the solstices, when the sun crosses over the celestial equator, and day and night are of equal length. Both the Jewish Passover and the Christian Easter are connected with the spring equinox, the actual day of celebration being determined by lunar phases. At the springtime the ancient Athenians celebrated the lesser Mysteries at Agrai, and six months later at Eleusis they held their greater Mysteries, which dealt primarily with death and the postmortem journey of the soul. Also near the autumnal equinox is Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year festival, followed ten days later by Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement for sins of the previous year.

SOLSTICES AND EQUINOXES

Midsummer ceremonies and festivals were held at henges and sacred sites throughout Britain and northern Europe, and the Medicine Wheel and Sun Dance rite of the North American Plains are also connected with the summer solstice.

These celebrations are but a sampling, which naturally prompts us to ask why they were linked to astronomical events: the result of earth's axis inclined in relation to its annual orbit around the sun. Part of the reason is that ancient cultures did not have the marked distinction between sacred and secular that we have today. At a more philosophical level, these rites were originally designed to aid them to reestablish or strengthen their connection with their divine source, to live in harmony with the cosmic ecosystem, and thus to participate consciously with the intelligent powers that create and sustain the universe.

Summer dawn cairn alignmnets at Big Horn Medicine Wheel, Wymoming (John A. Eddy, native American Astronomy; Aveni ed.)

For them, nature was the visible expression of divinity at work, and the ancient mythographers frequently associated the sky with universal mind or intelligence, which orders the structure and behavior of stars, planets, and all the creatures inhabiting them. The universe itself was considered to be a living entity in which all beings, including ourselves, were rooted, and drew life, meaning, and substance. For example, in Beyond the Blue Horizon, Dr. E. C. Krupp, director of the Griffith Observatory, writes about the Desana Indians of the Amazonian rain forest, a "primitive" people "who still look at the sky and still talk about it":

They speak of the sky as a brain. [It] is bicameral, divided into two hemispheres, and the fissure between them is the Milky Way. . . . Their brains must resonate with the sky, must dance to the same tune, for consciousness to exist . . . . They are guided by their own experience and by the insights of their shamans, whose direct, mystical experiences with the spirit world provide valuable understanding and power. The Desana shamans say they go to the sky for some of this power and knowledge. . . .

. . . One of its fundamental attributes — and the Desana are explicit about this — is a link between the brain and the sky. What the Desana mean by that link is the relationship they see between the celestial cycles that order time and the world, and their use of those cycles to organize their lives and response to the natural environment. . . . They and other people all over the world, since the stone age, have seen a correlation between what takes place in the sky and what is happening on earth and in their lives. — pp. 3-4

While each religious system and culture usually celebrates only one or two of the solstices or equinoxes, modern theosophical tradition links the four and shows their relationship to one another as major junction points in our evolutionary cycle. The writings of H. P. Blavatsky contain a few hints about the seasons (cf. The Secret Doctrine 1:639), but G. de Purucker gives a fuller development of this theme, most notably in The Four Sacred Seasons, relating it to the goals of life and the initiatory program of the Mystery schools.

Our English word initiation comes from the Latin root initiare, meaning "to begin." Initiation is also the word most frequently used to translate the equivalent Greek term, telete, which means "a finishing," a "making perfect" for that particular level of awakenment or insight. The sacred seasons accordingly mark beginnings and endings, each representing the close of an old and the opening of a new chapter in the larger continuum of our individual and collective evolutionary experience. The basic purpose of the initiatory Mysteries — which find their analog in the sacraments and liturgical practices of the Christian churches — is progressively to align oneself more closely with the god within. All real initiations are preceded by instruction, training, discipline, and purification. Taken together these are said to comprise the lesser Mysteries — the necessary foundation and rehearsal of the greater Mysteries, which lead to the mystic union with our divine source.

The greatest of the initiations, as the world's religious traditions suggest, occur at the solstices and equinoxes.

These four seasons in their cycle are symbolic of the four chief events of progress of initiation: first, that of the Winter Solstice, which event is also called the Great Birth, when the aspirant brings to birth the god within him and for a time at least becomes temporarily at one therewith in consciousness and in feeling; . . . the birth of the mystic Christos.

Then, second, comes the period or event of esoteric adolescence at the Spring Equinox, when in the full flush of the victory gained at the Winter Solstice, and with the marvelous inner strength and power that come to one who has thus achieved, the aspirant enters upon the greatest temptation, except one, known to human beings, and prevails; and this event may be called the Great Temptation. . . .

Then, third, comes the event of the Summer Solstice, at which time the neophyte or aspirant must undergo, and successfully prevail over, the greatest temptation known to man just referred to; and if he so prevail, which means the renouncing of all chance of individual progress for the sake of becoming one of the Saviors of the world, he then takes his position as one of the stones in the Guardian Wall. Thereafter he dedicates his life to the service of the world without thought of guerdon or of individual progress — it may be for aeons — sacrificing himself spiritually in the service for all that lives. For this reason the initiation at this season of the year has been called the Great Renunciation.

. . . in the initiation of the Autumnal Equinox the neophyte or aspirant passes beyond the portals of irrevocable death, and returns among men no more. . . .

The Autumnal Equinox is likewise straitly and closely related to the investigation, during the rites and trials of the neophyte, of the many and varied and intricate mysteries connected with death. For these and for other reasons it has been called the Great Passing. — The Four Sacred Seasons, pp. 42-5

It is easy to think of all this as too mystical, lofty, and remote from our day-to-day lives. Yet, viewing the natural cycle of birth, growth, maturity, and passing, one can see the very short distance between concept and application. Following the analogy of nature, I find it helpful to think of the solstices as turning points and the equinoxes as crossing points. Winter represents a turning away from the darkness of selfishness and ignorance towards the light of charity and spiritual perception. In one sense it symbolizes the birth, or rebirth, of the solar element in our nature as our guiding light in life.

The spring "cross over" may be seen as an opportunity to surmount the trials and temptations of our adolescence, both physical and spiritual, and to become self-reliant — more fully cognizant of and responsive to the inner and outer promptings of our divine center. In spring all nature seems to be trying to infill itself with the creative life force, to achieve wholeness and balance. With fall, it is natural to think of harvest: to reap, store, and assimilate its fruits, to let go of the past, and prepare for the future.

Coming back to the summer solstice — when the sun stands stronger, higher, and longer than at any other period of the year — one finds inspiration in the Great Renunciation, or what could be called the "bodhisattva" initiation. In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a person on the path to buddhahood who has awakened a degree of wisdom — bodhisattva means "one whose essence is wisdom." In this sense anyone who strives for enlightenment, who acts from his innermost essence, or wisdom and compassion, is to some extent a bodhisattva. The highest example is one who has earned the right to the eons-long bliss of nirvana but, choosing from the very law of his being, renounces it for a more noble objective: the eons-long task of working for the enlightenment and happiness of all.

The summer turning point in this sense represents a pivotal decision about evolutionary progress and fulfillment, in which all of us may participate. Do we "stand still" and stay awhile to help? Or have we become so energized by our aspirations that we cannot help but jump orbit into a more distant realm, more isolated from the needs of the world? As I see it, renunciation is a paradox. We turn away from personal spiritual progress, but in so doing we actually identify more closely with spirit. Everything hangs on motive: if our decision is made with a view to deferred benefit — a loftier nirvana, rank in heaven, or some other lordship — we instantly nullify the act because we have personalized it. Our daily life presents us with innumerable opportunities to act from compassion and self-forgetfulness, and hopefully we do this wisely. To the degree we succeed, we discover the meaning of renouncing the fruit of action, and perhaps something of the quality of experience undergone by the great ones at this summer solstice period. Surely they have no aspiration to be world saviors, but are so precisely because of the simplicity of their decision and what naturally flows from it. Similarly, by detaching ourselves from personal motive as far as possible, our highest wisdom and love can exert themselves — and the world around us will be benefited accordingly.

Simply put, summer symbolizes maturity and ripening judgment, when our natural interest turns to the needs of others. This solstice period is perhaps the sacred season to which we can most easily relate, because altruism and service is something all of us understand.

(From Sunrise magazine, June/July 1998; copyright © 1998 Theosophical University Press)