VII. TRISTAN AND ISOLDE.

(Concluded.)

Never shall yearnings torture him, nor sins

Stain him, nor ache of earthly joys and woes

Invade his safe eternal peace: nor deaths

And lives recur, he goes

Into Nirvana. He is one with Life.

Yet lives not. He is blest, ceasing to be.

om mani padme om! the dewdrop slips

Into the shining sea! — Light of Asia.All that is by Nature twain

Fears, or suffers by, the pain

Of Separation: Love is only

Perfect when itself transcends

Itself, and, one with that it loves.

In undivided Being blends.

— Solaman and Absal of Jami.

The Third Act introduces us to Tristan's ancestral castle in Brittany, whither the faithful Kurvenal has brought his wounded master out of reach of his enemy. It is significant that in his setting of this peculiarly Celtic legend Wagner takes us in turn to the ancient Celtic countries of Ireland, Cornwall, and Brittany.

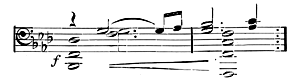

Tristan lies on a couch in the neglected garden of the Castle with the grief-stricken Kurvenal watching anxiously for signs of returning consciousness. For, since the blow dealt by the "Dweller on the Threshold," his soul has been wandering in other realms. The opening theme, in which we recognize the original Yearning-motive in a new form, impresses us at once with the heavy weight of woe and quenchless yearning which oppresses and tortures the soul:

From the battlements the melancholy tune of a herdsman playing on his pipe adds to the deep pathos of the scene:

Kurvenal, in utter despair at Tristan's condition, has at last sent to Cornwall for Isolde, as the only one who can heal him. The ship is expected hourly and the herdsman is watching for it, but as yet in vain. Presently the strains of the plaintive tune waken the sufferer and he asks Kurvenal in a hollow voice where he is. Kurvenal tells him how he carried him down to the ship and brought him home to his own land where he shall soon get well and strong. Alas! no more than Marke or Brangaene can this devoted man know aught of the inner life, as Tristan's answer shows:

Think'st thou so?

I know that cannot be.

But what I know I cannot tell thee.

Where I awoke I tarried not,

But where it was I cannot tell thee.

I did not see the sun.

Nor saw I land nor people.

But what I saw I cannot tell thee.

I — was — where I have ever been,

Where I for aye shall go, —

In the vast realm of the whole World's Night.

Here we find expressed the truth upon which in part the principle of Re-birth rests: that the soul has existed for ever in the past and will endure eternally in the future; for, as Wagner truly says, "that Future is not thinkable except as stipulated by the Past (Prose Works II. 376).

The temporary absence of Tristan from his body bears a close resemblance to the "descent into the Underworld" which in all ages a would-be initiate has had to undergo. And when we remember that the Tristan legend is a Solar Myth, Tristan representing the Sun, the connection becomes more obvious; for Wagner has throughout preserved the symbolic contrast between the Day as the World of Appearances and the Night as the Realm of Realities or the Mysteries.

"Astronomically," says H. P. Blavatsky, "this descent into Hell" symbolized the Sun during the autumnal equinox when abandoning the higher sidereal regions — there was a supposed fight between him and the Demon of Darkness who got the best of our luminary. Then the Sun was imagined to undergo a temporary death and to descend into the infernal regions. But mystically, it typified the initiatory rites in the crypts of the temple called the Underworld. All such final initiations took place during the night." (1)

In this journey to the inner world Tristan has found that the "Desire of Life" is not yet stilled. "Isolde is still in the realm of the Sun," and whilst this is so it is a sign that he cannot free himself from the bonds of the flesh:

I heard Death's gate close crashing behind me;

Now wide it stands, by the Sun's rays burst open.

Once more am I forced to flee from the Night,

To seek for her still, to see her, to find her

In whom alone Tristan must lose himself ever.

. . . .

Isolde lives and wakes,

She called me from the Night.

As Tristan sinks back exhausted the mystified and terror-stricken Kurvenal confesses to his master how he had sent for Isolde as a last resource:

My poor brain thought that she who once

Healed Morold's wound could surely cure

The hurt that Melot's weapon gave.

Tristan is transported at the news and urges Kurvenal to go and watch for the ship, which already he sees with the clairvoyant vision of one who is more than half free from the limitations of Time and Space. But Kurvenal reports that, "no ship is yet in sight," and as the mournful strain of the herdsman is resumed Tristan sinks yet deeper in a gloomy meditation which impresses us with the most profound sadness. It rouses in him the memory of his present birth in words which recall the sorrow-laden lot of Siegfried's parents:

When he who begot me died,

When dying she gave me birth,

To them too the old, old tune,

With the same sad longing tone,

Must have sounded like a sigh;

That strain that seemed to ask me,

That seems to ask me still,

What fate was cast for me,

Before I saw the light, what fate for me?

The old sad tune now tells me again —

To yearn! to die! To die! to yearn!

No, ah no! Worse fate is mine;

Yearning, yearning, dying to yearn,

To yearn and not to die!

These latter lines have, perhaps, more than any other part of the drama, been ascribed to Schopenhauer's influence; but I have already shown that Wagner had already grasped intuitively the great philosopher's main principles long before he became acquainted with his writings. His own account of this is clearly given in his letter to August Roeckel which I quoted in the concluding article on the Ring of the Nibelung. The above lines are a close reproduction of the passage from the Artwork of the Future which I placed at the head of my last article, where Wagner speaks of the soul "yearning, tossing, pining, and dying out, i.e., dying without having assuaged itself in any 'object', thus dying without death, and therefore everlastingly falling back upon itself." And in his Communication to My Friends (Prose Works, Vol. I.) he says that at the time of working out his Tannhauser he was feeling a deep disgust of the outer world and a yearning for "a pure, chaste, virginal, unseizable and unapproachable ideal of love. . . . a love denied to earth and reachable through the gates of death alone."

It is by no means the least valuable part of the rich heritage that Wagner left to the world that he has laid bare some of his inner life, and so enabled us to see that the essential principles of his dramas are distilled from his own soul experience. If this be egotism, as some narrow critics allege, would that there were more of it in the world!

In the course of Tristan's reverie we come to the point where we learn the psychological significance of the love-draught which he shared with Isolde and which is still torturing him with the curse of "Desire that dies not":

Alas! it is myself that made it!

From father's need, from mother's woe,

From lover's longing ever and aye,

From laughing and weeping from grief and joy.

I distilled the potion's deadly poisons.

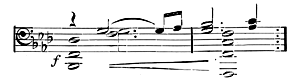

The concentrated power of this terrible Desire-Curse here finds expression in the following theme, many times repeated.

Overcome once more Tristan sinks back fainting upon his couch. Presently his inner sense again perceives the nearer approach of Isolde, and soon a joyous strain from the herdsman is followed by the news that the ship approaches from the North. Kurvenal reluctantly leaves his master to meet Isolde and help her to shore, and the old impatience overmasters Tristan again. In a fever of excitement he tears the bandage from his wound and staggers forward, crying:

In blood of my wound Morold I once did slay;

In blood of my wound Isold' I win today.

(Isolde's voice is heard without)

How I hear the light! The torch — at last!

Behold it quenched! To her! to her!

He rushes headlong towards Isolde and sinks in her arms to the ground; and as he raises his dying eyes to hers with the one word "Isolde," we hear the Look- motive for the last time. Night has indeed come at last for Tristan. But in the right way? No, as we are reminded by Isolde's lament:

Ah! not of the wound, die not of wound.

To both united be life's light quenched.

Tristan .... look ....

In his eye .... the light ....

Beloved! .... Night!

She falls senseless on his body, and now a tumult is heard and the herdsman announces to Kurvenal the arrival of a second ship, bearing King Marke, Melot, Brangaene, and others. Kurvenal, eager to avenge Tristan's death, rushes out and furiously attacks Melot as becomes to the gate, striking him down; then, driven back wounded by Marke and his men, he staggers to Tristan's body and falls dead beside it with a touching expression of fidelity.

Tristan, dear master — blame me not —

If I faithfully follow thee now!

Gazing mournfully on the solemn scene, King Marke utters these words of sad reproach:

Dead, then, all! All — dead!

My hero, my Tristan, most loved of friends,

Today, too, must thou betray thy friend?

Today when he comes to prove his truth.

For, as Brangaene now relates, the King had sought from her the meaning of the riddle, and, learning of the love-draught, had hastened to repair the wrong which had been wrought through Tristan's own delusion. To Isolde, now awakening from her swoon, he speaks and tells her of his noble purpose. But Isolde seems already unconscious of what is passing around her, and begins softly to whisper in the melting strains of the Death-Song the revelation of the great truth which was glimpsed by Tristan in the culmination of the second act. Until now we had felt a fear that the soul had made a fatal mistake in its over haste; but, as this wondrous song proceeds, we realize that in the transfigured woman who utters it there is embodied that divine power which shall restore the balance and bring peace and rest in Union with the All. Thus the great song rises ever in power and grandeur until at last the World-Union motive bursts forth like a shout of victory with the magnificent concluding words:

Where the Ocean of Bliss is unbounded and whole,

Where in sound upon sound the scent-billows roll,

In the World's yet one all-swallowing Soul;

To drown — go down — To Nameless Night — last delight!

Then as the great theme gradually dies away, and with the last breath of the Yearning-motive is dissolved in ethereal harp sounds, Isolde sinks lifeless on Tristan's body and the Tragedy of the Soul is once more accomplished. But this is no ending of untold sadness; rather is it one in which we see the soul, purified, free from the shackles of the body, rise triumphantly on the wings of Love and Knowledge into that realm of deathless consciousness clearly indicated by the great Master as the only possible goal of man's life struggles. A sense of triumph, of the most utter liberation, is left with us as we close this page of the Master's works, realizing ever more and more the deep teaching which he sought to convey: that life is indeed not a cry of agony but a Song of Victory.

Finally let Wagner sum up the whole drama for us in a fragment from his own pen: "Desire, desire, unquenchable and ever freshly manifested longing, — thirst and yearning. One only redemption. — Death sinking into oblivion, the sleep from which there is no awaking! It is the ecstasy of dying, of the giving up of being, of the final redemption into that wondrous realm from which we wander furthest when we strive to take it by force. Shall we call this Death? Is it not rather the wonder-world of Night, out of which, so says the story, the ivy and the vine sprang forth in tight embrace, o'er Tristan and Isolde's tomb?

FOOTNOTE:

1. Roots of Ritualism in Church and Masonry, Lucifer. Vol. IV. p. 229. (return to text)